Identifying Devices by their MAC Address

Ever wondered how your router knows your iPhone from your smart fridge, or how coffee shop Wi-Fi remembers you? It all comes down to the MAC (Media Access Control) Address.

While an IP address is like your mailing address (where you are currently located), a MAC address is like your social security number—a unique, permanent ID hard-coded into your device's network hardware.

In this post, we’ll explore how to identify devices using these digital fingerprints and why the rise of Private MAC addresses is changing the game for privacy.

Anatomy of a MAC Address

A MAC address is 48 bits long, and written in hexadecimal format, which means it can use all the numbers plus A to F of the letters. They are often split with colons, somtimes hyphens, and sometimes nothing at all!

00:1A:2B:3C:4D:5E00-1A-2B-3C-4D-5E001A2B3C4D5E

All of these are the same MAC address.

The MAC address is split into two sections. The first 6 characters (24 bits) represent the manufacturer, and this is called the OUI. The second 6 characters is the unique device ID.

Let's look at my wireless card MAC address, which has an OUI of 60:E3:2B. This translates in binary to:

0110 0000 : 1110 0011 : 0010 1011

I've left the colons in for ease of reading, but we're going to focus on the two least significant bits of the first byte. These are known as the control bits.

Bit 0 (the rightmost bit) is the Individual/Group (I/G) bit. This tells the network whether traffic is meant for one device or a group. The bit is 0, which means it is an individual address.

Bit 1 is the Universal/Local (U/L) bit. This determines whether the address is a hardware address (universal), or a software address (local). Because the bit is 0, this is a Universal address.

In contrast, a broadcast MAC address (FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF) would have a control bit of:

1111 1111

This would translate to a group, local address. In other words, the traffic is meant for a group and the MAC address has been set by software, not hardware.

This will be important when we look at Private MAC Addresses shortly.

The second and third bytes of a MAC address are what are used to determine the manufacturer. The IEEE Registration Authority is in charge of assigning OUIs to manufacturers.

Lookup Databases

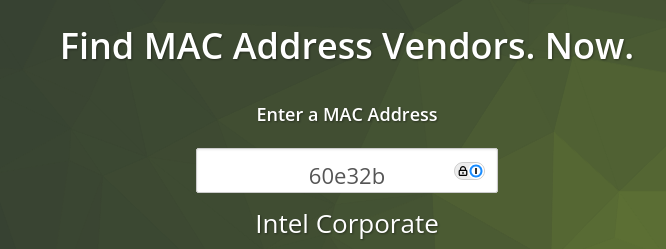

Now we know the first half represents the manufacturer, we can use that to lookup what kind of device we are looking at. For example, the first half of the MAC address of my wireless card is 60:E3:2B. Using the website https://macvendors.com/, I can see that the manufacturer of my wireless card is Intel.

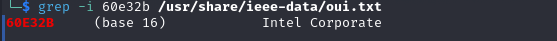

That's quite a manual process. What if we want to script it, such as take a packet capture and deduce what kind of devices are involved? There are numerous databases pre-installed on Kali. The one I use most frequently is at:

/usr/share/ieee-data/oui.txt

There is also a CSV at the same location. But by using grep, and the text file, we can get the same results as from the website.

This really handy, now I can see what I'm dealing with on my network! Except, of course, if it is using a Private MAC Address.

Private MAC Addresses

People don't want to be tracked, and the MAC address provides an easy way of doing that. Your IP address can change, maybe you've been away and your DHCP lease expired. No matter, here's a new IP address. But your MAC address stays the same.

Modern operating systems now have privacy built in by default. iOS, Android and Windows all now use Private MAC addresses by default. This means each time the device connects to a network, the device assigns a temporary MAC address and gives the network that. Networks can no longer track a device by its MAC.

I'll go into how this presents challenges for network administrators in a second, but firstly, how do we identify a Private MAC Address?

You can often tell if a MAC address is randomized just by looking at the second character. If the second digit is 2, 6, A, or E, it is almost certainly a Private MAC Address. This works because of the way MAC addresses are constructed, and we go back to the control bits.

Let's examine the OUI of the MAC address of my phone, first in hexadecimal, then in binary

2E:FE:FF -> 0010 1110 : 1111 1110 : 1111 1111

The I/G bit is 0, and the U/L bit is 1. This means the address is an individual, locally administered address. The only way to get these control bits is if the second character is 2, 6, A or E.

2: 00106: 0110A: 1010E: 1110

If you try and lookup that address in the OUI database, it will return no results. These address blocks are reserved by the IEEE and not assigned to any manufacturer. Anyone is free to use them as a temporary address.

So how does this affect network administrators? I manage a large enterprise wireless network, with a large element of BYOD devices, most of them phones. Each time these phones connect, they change MAC address, which means they get a new DHCP lease. Each phone can roam around, connecting again and again, consuming multiple IP addresses in a short space of time and taking out large chunks of the DHCP scope. In theory iOS and Android only allocate one private MAC per SSID, but if the user forgets the network it will reset. The MAC also periodically rotates.

It also means troubleshooting tools are practically useless. If a user has a phone that won't connect, I can't look back to see if it has failed to connect before because I don't know what MAC address it was using. My wireless dashboard also registers a new device each time it connects, meaning the stats for one phone are split over multiple entries.

To combat this, I have drastically shortened the DHCP lease times on BYOD networks to 8 hours, down from 5 days. This automatically frees up IP addresses that are no longer in use.

Conclusion

Understanding the makeup of MAC addresses is a powerful diagnostic tool to have in your armoury. It allows you to identify the devices communicating on your network, and understand how the makeup of the address influences how the frame behaves on a network.

The rise of Private MAC addresses represents a major shift in the networking landscape. While these randomized identifiers are a victory for consumer privacy, they present a significant "identity crisis" for network administrators. Recognizing the 2, 6, A, or E pattern allows you to instantly distinguish a physical hardware identity from a temporary software-generated one.

Comments