Session Hijacking: Methods and Mitigations

In the last post I looked at all the different methods of multi factor authentication, and evaluated the strength of each type. Passkeys came out as a clear winner, as they mitigate both fake domains and users being tricked into giving out their one time passcode.

So why is identity protection still such a problem for administrators? Firstly, abusing valid accounts (often via stolen session tokens or credentials) was the primary entry vector for cloud incidents, accounting for 35% of all cloud intrusions, and secondly, the average cost of a data breach in 2025 was $4.44 million, albeit down from $4.88 million in 2024.

Part of this issue is session cookies. Once the authentication is done, the user is given a cookie that it stores in the browser telling the identity provider that they’re already authenticated. If an attacker can copy this cookie, they don’t need to crack MFA because they’re already logged in.

One of the most famous examples of this was Firesheep, a Firefox extension that stole the session cookies of everyone on the same public WiFi network, then let the attacker access all the logged in social media accounts. This was done to prove that transmitting session cookies in plaintext was insecure, and thankfully that is no longer common practice.

In this post I’m going to look at how session hijacking works and then look at what is being done and can be done to mitigate it.

Ready? Let’s go.

Table of Contents

How Session Hijacking Works

Thanks to Firesheep, transport is now secure. No-one is using HTTP anymore, everything is encrypted with TLS and gets a nice padlock in the browser. Sniffing network traffic is still fruitful as an attack vector, but an attacker can no longer see exactly what is being sent, so they target the endpoint. Below are two examples of how that can be done, but there are other methods.

Infostealer Malware

Lumma Stealer is probably the market leader in the infostealer sector. It is a highly effective session cookie stealing malware that has been used in various campaigns to great affect. Microsoft have written about it here. It uses increasingly creative ways to reach victims, including fake CAPTCHAs that instruct the users to perform actions, malvertising for products such as Notepad++ that lead to fake downloads, or simply hosting it on GitHub disguised as a useful tool and waiting for the user to come to them.

Once installed, it targets Chromium bases browsers to steal passwords, data, and session cookies, while also scanning for crypto wallets.

This fascinating podcast talks in detail about how Microsoft leveraged various laws to disrupt and take Lumma Stealer down. It may still come back, and there are other infostealers out there that pose a session hijacking threat.

Reverse Proxy

Instead of building a fake login page, attackers build a proxy server which mirrors the real login page to the victim. The victim logs in as normal, and the real identity provider authenticates them as usual, with both parties unaware that the authentication is being intercepted. The resulting session cookie is hijacked and sent to the attacker.

This method beats HTTPS because the victim has a secure connection, except it's with the attacker rather than the identity provider. The attacker is capturing the password and MFA token and forwarded them to the real login page, and then capturing the results as they come back. Evilginx2 is probably the most well known tool for this attack.

Passkeys can mitigate this as well, because the challenge doesn’t come from the correct domain it won’t sign it. Even though proxy forwards the original challenge, the browser enforces origin checks, ensuring the domain in the challenge matches the domain in the address bar. If the proxy domain micros0ft.com but requests a signature for microsoft.com, the browser blocks the request immediately.

Mitigations

Device-Bound Session Credentials (DBSC)

We’ve established that if the attacker can take the session cookie, they can recreate the session on their own device without the need to authenticate. So how can we protect against that?

Google and Microsoft are backing a new W3C standard called Device-Bound Session Credentials (DBSC). This new protocol cryptographically ties a session to a device, preventing it from being transferred.

It does this by using the device's TPM, and a public/private key pair. The private key is stored in the TPM and can’t be exported. Periodically it is used to sign a challenge issued by the server, proving that the device is still the same device that signed in.

Although adoption is ongoing, once universal, this protocol will secure session credentials to the device's hardware, rendering stolen cookies useless to an outside attacker.

Primary Refresh Token

The primary refresh token (PRT) operates on a similar concept to DBSC - it binds the session to the device. When the user logs in to Windows, Microsoft Entra ID issues a PRT that is bound to the device using a public/private key pair. Think of the PRT as the modern equivalent of the Kerberos Ticket-Granting-Ticket; it lets the user authenticate to other Microsoft services without needing to enter credentials, but every time it is used it must sign a challenge using the private key stored in the TPM. This ensures that the PRT is still being used on the device it was issued.

Conditional Access

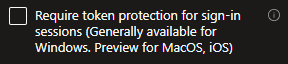

Both DBSC and PRT rely on devices having TPMs. If a device doesn’t have a TPM, the session cannot be bound to it and remains vulnerable to hijacking. Microsoft have introduced a conditional access policy control that requires sessions to be device bound.

Microsoft currently binds logins where possible, but still allows them when it isn’t. This policy will disable logins where binding isn’t possible.

You can check in the Azure Sign-in logs if a session is device bound or not. In the basic info tab, look for ‘Token Protection - Sign In Session’. I checked a user on their managed device and it says bound:

I checked the same user on their personal device:

Another nail in the coffin for personal devices.

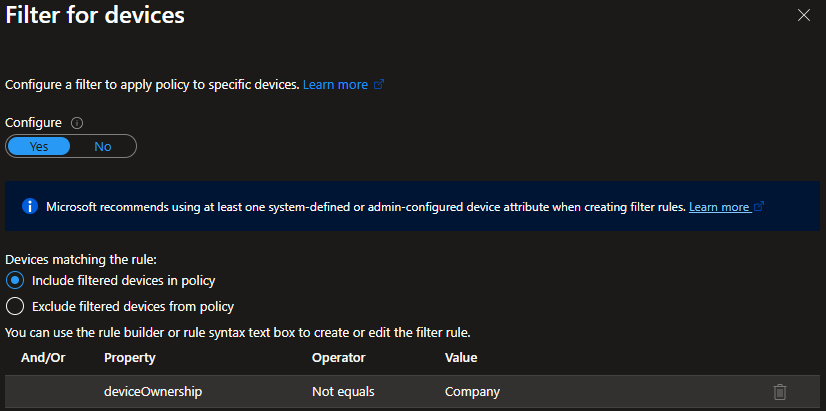

Conditional access policies can also be used to prevent unmanaged devices, either completely or for specific apps. This means that unbound sessions hijacked from managed devices cannot be moved to unmanaged devices, adding that extra hurdle for attackers to gain access.

While PRT has traditionally been only for enterprise level protection, DBSC is bring the benefits to consumers and unmanaged devices, meaning administrators can be slightly more confident in users logging in from personal devices.

Conclusion

The arms race continues. Attackers crack passwords, defenders introduce MFA. Attackers breach sessions, so defenders improve session security. Device binding is the next logical step for identity security.

It is important to note that DBSC will stop attackers using sessions on their own machines. It will not stop them performing actions on users machines if the machine is compromised. Endpoint security remains a key part of organisational defences. It also possible that an increase in phishing using Virtual Desktop Infrastructure (VDI) will rise, tricking users into authenticating on browsers managed by the attacker instead of the local machine.

However, what is proven is that MFA on its own is no longer enough. Identities are continually vulnerable and attackers will find many and various ways to gain access. Administrators need to ensure that their inventory have TPM 2.0 chips and sessions are securely bound, and address the coverage gap on devices that are not able to utilise hardware backed session binding.