A Practical Guide to IPv6

IPv6 has been around for decades now. The reasons for it are well known; IPv4 simply does not have enough address space to accommodate the modern internet.

A quick recap - an IPv4 address is 32 bits, which equates to roughly 4.3 billion unique addresses. IPv6 is 128 bits, which is so vast it is practically unlimited - 340 undecillion unique addresses. It is a number almost inconceivable large - there are one septillion trillions in an undecillion.

So in theory, problem solved. we now have enough addresses for every human on earth to have 41 sextillion addresses each. But while IPv6 is dominating some sectors, others are lagging behind.

Mobile carriers and hyperscalers are largely using IPv6 now, but the majority of private networks are still using IPv4.

The hiccup in the IPv6 rollout came with the introduction of Network Address Translation, or NAT. This allowed entire networks to hide behind one public IP address, reducing the amount of addresses needed by organisations. This IPv4 life support system was so successful that IPv4 is still a viable option three decades later.

IPv6 does not use NAT, so each device needs a publicly routable IPv6 address.

In this post I’ll explain how IPv6 addresses are formulated, and what a network would need to do to transition from IPv4 to IPv6.

Table of Contents

IPv6 Structure

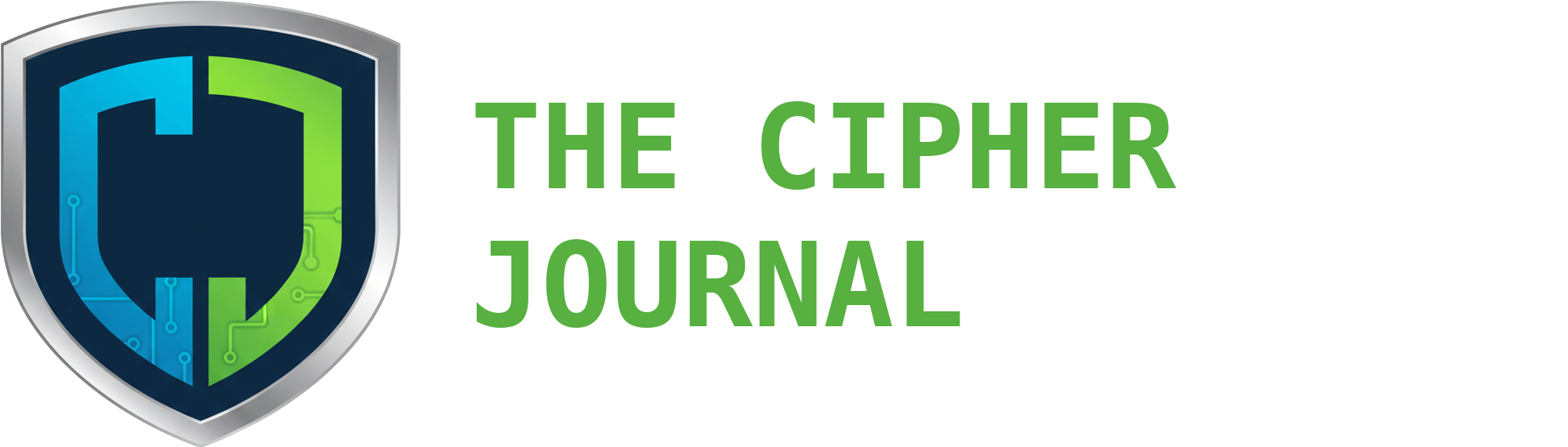

IPv4 addresses are logically structured into 4 groups of 8 bits. IPv6 addresses are structured into 8 groups of 16 bits, and each group is called a hextet. Because this would be an arduous task to write out, IPv6 is expressed in hexadecimal form, so each group can be shortened to 4 digits.

Let’s look at an example address:

2001:0db8:85a3:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334

This is the full IPv6 address expressed as binary:

0010000000000001:0000110110111000:1000010110100011:0000000000000000:0000000000000000:1000101000101110:0000001101110000:0111001100110100

Thank god for hexadecimal.

However, there are two rules that can be used to shorten IPv6 addresses. The first rule is:

Rule 1: Drop all leading zeros.

You might have seen IPv6 addresses that don’t have 4 hex characters in each group. This is because any leading zeros are dropped from the notation, so the address above becomes:

2001:db8:85a3:0:0:8a2e:370:7334

We can also omit any sections of all zeros, but this can be done only once.

Rule 2: Shorten any consecutive all-zero groups to ::

The address now becomes:

2001:db8:85a3::8a2e:370:7334

The double colon is restricted to a single use because it acts as a placeholder for an unknown number of zeros. If an address contained two double colons, a computer wouldn't know how to distribute the missing hextets between them.

For example, if an address is missing 5 groups of zeros, it wouldn't know if the first :: represents 2 groups and the second represents 3, or vice versa. Restricting it to one use ensures there is only ever one mathematical solution to expand the address back to its full 128-bit length.

The best practice here is to use the double colon rule once, and use it on the longest string of zeros. If you have two equal groups of zeros, shorten the leftmost one.

IPv6 Subnets

IPv6 is classless, instead using CIDR notation to indicate where the network segment of the address ends.

A standard IPv6 address has a /64 prefix. This means the first 64 bits (4 hextets) are the network, and the rest is for the host. Within the network segment, the last hextet is reserved for subnets.

An ISP will typically give an organisation something called the Global Routing Prefix, which is the first three hextets, making it a /48 IPv6 address.

If we look at the address we used previously, we can see the Global Routing Prefix is:

2001:db8:85a3::/48

Remember, all the other zeroes can be shorted to ::. This is equivalent to a 10.0.0.0/8 IP address. The first octet is defined, the rest are zero and can be changed.

The organisation can now add the subnet hextet, making it a /64 address:

2001:db8:85a3:1::/64

2001:db8:85a3:2::/64

2001:db8:85a3:3::/64

An ISP will typically give either a /48 or a /56 address block to a router. The /56 gives 8 bits of subnet space, which is 256 available subnets and is typically assigned to residential customers, whereas the /48 gives 16 bits of subnet space, which is 65,536 subnets. This is normally assigned to enterprise customers.

IPv6 Host Address

Another big change in IPv6 is the way hosts get their unique address. Previously, devices relied on either a manual static configuration or a DHCP server to get an IP address. With IPv6, they can decide themselves.

They do using a process called Stateless Address Autoconfiguration (SLAAC). This allows a device to join a network, ask a router what the network address is, and then generate its own host ID to complete the IPv6 address.

There are two methods the host uses to create the ID.

SLAAC - EUI-64

This method calculates the ID using the host MAC address.

Step 1: Take the MAC Address

00AABBCCDDEE

Step 2: Split it in half and insert FFFE in the middle.

00AABBFFFECCDDEE

Step 3: Flip the 7th bit of the first byte (the universal/local bit)

02AABBFFFECCDDEE

Step 4: Append the ID to the network address

2001:db8:85a3:1:02aa:bbff:fecc:ddee

Because MAC addresses are unique, this is a great way of creating unique host address on a network.

However, because IPv6 addresses are not hidden by NAT, this has privacy implications as services will be able to easily track devices across the internet, so another method was developed.

SLAAC - Privacy Extensions

To counter the privacy issue, RFC 4941 was introduced to allow for temporary addresses. A device generates a random 64-bit number and uses that as the host ID. This number is changed every few hours, making it impossible for service to use IP address as a way to track a device.

Duplicate Address Detection (DAD)

The chances of two devices generating the same 64-bit number is astronomically rare, but theoretically not impossible, so devices check before they commit to an address.

The device generates the ID and creates the address, but marks it as tentative. While it is in this state, the device cannot receive normal traffic.

It then sends a Neighbor Solicitation message to a special multicast address asking if anyone has that address. If no-one responds with a Neighbor Advertisement after 1 second, the device assumes that the address is available and changes it from tentative to preferred.

DHCPv6

SLAAC allows devices to join a network independently, and use Neighbor Solicitation to find the address range and the gateway address. DHCPv6 is used where organisations still want the centralised control over their network.

DHCPv6 can be either Stateless or Stateful. In Stateless mode, the device will use SLAAC to create it’s IPv6 address, then get other information from the DHCP server, such as DNS server addresses and domain names.

In Stateful mode, the DHCP server decides which IPv6 address a device gets and maintains a state table of active leases.

Instead of DORA (Discover, Offer, Request, Acknowledge) DHCPv6 uses a process called SARR.

- Solicit: The client sends a multicast address to find any DHCPv6 servers.

- Advertise: The server responds with any available settings.

- Request: The client asks the server to officially assign the address/settings.

- Reply: The server confirms the assignment.

IPv6 Address Types

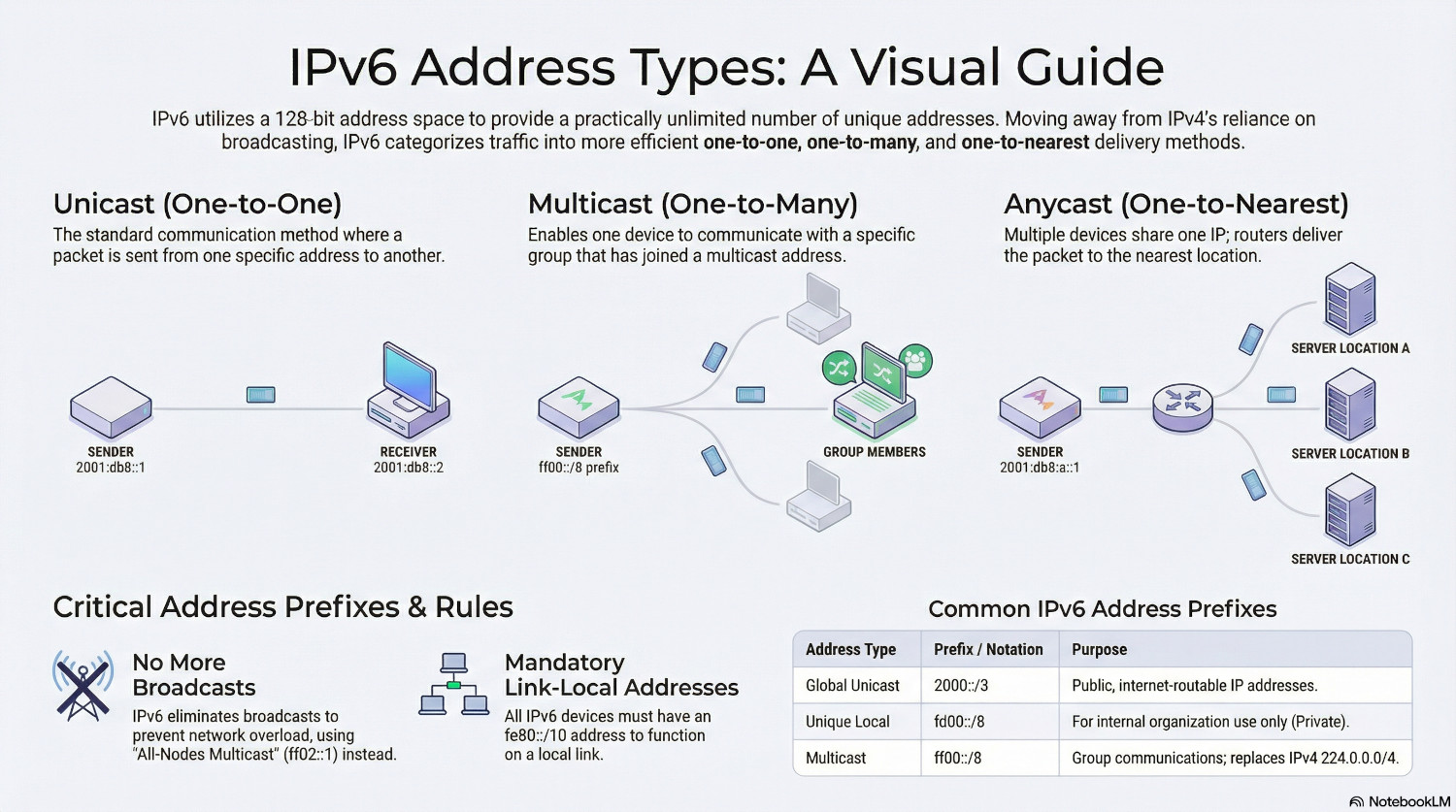

IPv6 address are split into three categories; Unicast, Multicast and Anycast. Note the lack of broadcast.

This is because IPv6 subnets are typically so vast that a broadcast packet would be sent to an indescribable amount of addresses. Broadcasts from multiple devices would quickly overload a network.

Because there are so many addresses available in IPv6, packets need to be more explicit when specifying their destination.

Unicast (One-to-One)

Unicast addresses are the standard address used for communication. A packet is sent from one address to a single other address.

There are a few different types of unicast address in IPv6:

Global Unicast | 2000::/3 | Public IP Address, routable on the internet

Unique Local | fd00::/8 | Internal Use Only

Link-Local | fe80::/10 | Similar to APIPA (169.254.0.0/16)

Multicast (One-to-Many)

Multicast addresses are used for one device to talk a group of devices. Devices must join a group, and the group is given a multicast IP address.

IPv4 multicast addresses are 224.0.0.0/4.

IPv6 multicast addresses are ff00::/8.

Typically, all devices join a group called All-Nodes Multicast. This has the address ff02::1, and would be the closest equivalent to broadcast.

Anycast (One-to-Nearest)

An anycast address is used where multiple devices are configured with the same IP address, and the sender wants to talk to any one of them.

The routers has multiple paths to an address because it exists in multiple locations, and it picks the shortest path.

Because there are so many addresses available, a device is able to have multiple IPv6 addresses. All devices must have a Link-Local address (fe80::/10) to function.

Neighbor Discovery Protocol (NDP)

ARP is dead in IPv6, replaced by Neighbor Discovery Protocol.

NDP replies on five specific ICMPv6 message types to manage communication:

| Message Type | Sender | Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Router Solicitation (RS) | Client | The client wants to know the network prefix |

| Router Advertisement (RA) | Router | The router gives out the network prefix |

| Neighbor Solicitation (NS) | Any device | Query an IPv6 address to find the MAC address |

| Neighbor Advertisement (NA) | Any device | Return a MAC address to an NS query |

| Redirect | Router | Used to suggest a better path to a destination. |

Adoption Techniques

Migrating from IPv4 to IPv6 presents several challenges and needs careful consideration for network administrators. The main challenge is that IPv6 is not backward compatible with IPv4, meaning IPv6 only devices cannot talk to IPv4 only devices.

There is also no tangible benefit for the end user (or the CFO). It doesn’t make websites load faster. It doesn’t present massive cost savings. Persuading organisations to migrate lacks a killer reason, but that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be done. The death of NAT simplifies firewall rules and removes complexity when merging networks. Routing is cleaner and faster. No broadcast messages mean devices are only processing packets meant for them.

There are three main techniques that can be used to ease the transition.

Dual-Stack

Dual-stack is the most common approach for enterprise. In this setup, every network device simultaneously runs both IPv4 and IPv6. If a DNS query returns an IPv6 address, the device will use it’s IPv6 network stack to communicate.

This approach is the most reliable, as if IPv6 doesn’t exist on a destination, IPv4 is still there to pick up the slack. It does, however, double the management overhead for administrators.

Tunneling

This approach encapsulates IPv6 packets in IPv4 headers, or vice versa. It allows a packet to traverse between IPv4 and IPv6 networks.

This technique adds overhead and increases packet sizes which can lead to fragmentation issues, and it relies on 6to4 or 4to6 tunnels.

Translation

This is when a device using one IP version needs to talk to a device using the other version. There are two types, either DNS64 or NAT64.

In DNS64, the DNS server creates an IPv6 address for an IPv4 only destination. In NAT64, the router strips the IPv6 header and replaces it with IPv4.

Conclusion

The internet of the future will see the rapid explosion if IoT continue, as well as mobile devices and AI demands all continue to stress out the address space available on IPv4. The demand for addresses will increase, and as organisations increasingly start charging for IPv4 addresses, organisations will migrate more and more to IPv6, at least for outside.

For inside, IPv4 will stick around for along time yet. Until the overheads involved in translating between the two versions becomes too costly to countenance for administrators.

In the meantime, sysadmins are going to need to know both.